- Home

- Jane Delury

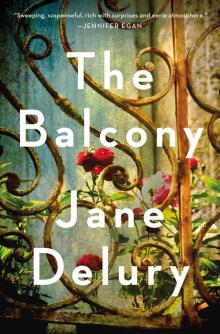

The Balcony

The Balcony Read online

The characters and events in this book are fictitious. Any similarity to real persons, living or dead, is coincidental and not intended by the author.

Copyright © 2018 by Jane Delury

Cover design by Ploy Siripant

Cover photograph by David Page / Arcangel

Cover copyright © 2018 Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Author photograph by Howard Korn

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the author’s intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact [email protected]. Thank you for your support of the author’s rights.

Little, Brown and Company

Hachette Book Group

1290 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10104

littlebrown.com

twitter.com/littlebrown

facebook.com/littlebrownandcompany

First ebook edition: March 2018

Little, Brown and Company is a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The Little, Brown name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

The following stories first appeared, in different form, in Narrative (“Nothing of Consequence”), The Southern Review (“The Pond”; original title: “Transformation of Matter”), The Yale Review (“Between”; original title: “Careful, Don’t Slip”); Crazyhorse (“Ants”), IOU: New Writing on Money (“Plunder”), StoryQuarterly (“A Place in the Country”; original title: “Autumn Harvest”); and Prairie Schooner (“Eclipse”).

Lyrics from “Moments in the Woods” hyperlinked here are from Into the Woods by Stephen Sondheim.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

ISBN 978-0-316-55466-4

E3-20180214-NF-DA

Contents

Cover

Title

Copyright

Dedication

Au Pair

Eclipse

A Place in the Country

Plunder

Nothing of Consequence

Half Life

The Pond

Tintin in the Antilles

Ants

Between

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Newsletters

For Cecilia Delury

Au Pair

In June of 1992, I left Boston for France with everything in front of me. For the next two months, I would be an au pair to Hugo and Olga Boyer’s daughter, Élodie, at their country estate near Paris. The position came to me through my advisor at Boston University, where I’d just finished a master’s degree in French and where Hugo would join the faculty in the fall. As Olga explained to my advisor, who asked me if I was interested, she and Hugo needed a jeune fille to help Élodie practice her English and to watch her mornings while Hugo worked on his book and Olga prepared the house for their departure. I would have a large, sunny room on the top floor and my afternoons and most of the weekends off. “Paris, with all of its delights, is only a brief train ride away,” Olga wrote to me in French, her handwriting large and baroque. “Élodie is an easy child, and her father and I are not monsters.” With the money I’d make, I could spend a third month in Paris and then see how I might stay on in France, where I believed I was meant to live.

When my advisor had mentioned a country estate, I imagined periwinkle shutters and roads lined with plane trees, fields of poppies and sunflowers, a village of church bells and cobblestone streets. Though I’d only been to Paris and to Nice, I thought I had an understanding of the French countryside, informed by the paintings of the impressionists and by novels such as Madame Bovary. The village of Benneville, however, turned out to be an industrial wash of smokestacks and faceless apartment buildings that ringed a center of ratty stucco storefronts. During the Second World War, Benneville had sat in the occupied zone, and the U.S. Air Force bombed the train station, missing their mark. The attack flattened the historic town center and shattered the church’s stained-glass windows, now replaced by clear panes. There was the requisite monument to the wars, and the requisite square where pigeons pecked gravel around a fountain, and old people sat on benches, looking lonely. As for the Seine, that same river that glided through Paris under the Pont Mirabeau, inspiring poets and painters, looked sullen and stagnant in Benneville, the banks cluttered with factories.

The manor, as Olga referred to the house and grounds that composed the estate, was a five-minute drive from the village, protected from the surrounding ugliness by the pines and oaks of a forêt domaniale. Clearly, the house—a bourgeois manoir of buttery limestone that stretched three stories into slate turrets and gables—had once been magnificent, but it had been hastily and cheaply remodeled in the 1970s. Past the grand doors, the historic charm gave way to flocked wallpaper, chartreuse tile, and malachite linoleum. The questionable remodel hadn’t been helped by Olga’s predilection for knickknacks. A collection of ornate mantel clocks sat on the parlor shelves under a row of vintage perfume bottles. Ancient kitchen implements—a candle mold and poissonnière, a moulin à légumes, chalky with rust—cluttered the dining room walls.

“This is what happens when you lose everything to a war,” Hugo told me as he carried my suitcase inside that first day. He skirted a stack of Turkish carpets rolled up like sausages.

“Très drôle,” Olga said. “I was a single woman in an enormous house for years and years,” she told me. “I needed to fill the space.”

We climbed the marble waterfall of a staircase, Élodie’s hand in mine. She was tiny for a four-year-old, with eyes the color of pennies and skin so pale that you could see a branch of veins on her right cheek. She’d adopted me instantly at the airport. On the drive to Benneville, she taught me the game of barbichette. She held my chin and I held hers, and the first one to laugh got a light slap on the cheek.

“Hugo and I are down that hall,” Olga said on the second-floor landing, “with Élodie next door.”

“I have a train set,” Élodie said. “Maman set it up for me. It runs all the way under the bed.” She squeezed my hand to punctuate her point.

Many of the ten bedrooms, Olga said as we went up the next flight, remained in the same triste état, or sad state, in which they’d been when she inherited the manor. “Thus all of the closed doors.” She was determined, she said, to hold on to the house and the grounds, but the upkeep of a property like this one cost a fortune.

“If you hear thumping at night, don’t fear ghosts,” Hugo said. “It’s only the pipes.”

On the third floor, we walked into a room big as my entire apartment in Back Bay.

“Et voilà,” Olga said, “votre petit coin de paradis.”

French doors, open like most of the windows in the house, led to a balcony with a view of the forest. I could imagine a gilded dressing table and four-poster bed, although the current décor consisted of a vinyl armoire that closed with a zipper and a lumpy, high bed covered with a paisley duvet.

“It’s the prettiest room,” Olga said. “It was mine for years.”

Hugo set down my bags. “Vous n’êtes pas dépressive, j’espère. We specifically requested a young woman in good mental health.”

“Stop that, Hugo,” Olga said. Once, she explained to me matter-of-factly, the lady of the house had jumped off the balcony, where Élodie had gone and was

now calling to me to come join her. “Madame Léger had been in her youth a famous courtesan, a grande horizontale of the Second Empire. She was forty when she died. It was said that she hadn’t taken well to the aging process.”

“It might have only been meant as a dramatic gesture,” Hugo said. “She had a réputation de folle. It is only three stories. Only she landed poorly and broke her neck.”

“Don’t worry,” I said, as I went to join Élodie. “I grew up in the Midwest. We don’t go crazy.”

“Hemingway aside,” Hugo said.

I had tried to be clever and he had outclevered me. I was used to this kind of behavior from men in academia. I was a good student of French—solid in my verbal constructions, even the plus-que-parfait, versed in the gender distinctions of nouns. My accent was passable. My graduate school papers on Flaubert’s love letters and the symbol of the corset in the nineteenth-century novel received As. But I was not brilliant. I would have preferred in some ways to be terrible.

Outside, Élodie stood on her tiptoes on the balcony, looking over the iron railing, which was supported by spindles that looped and twisted in a rusted web.

“Il y a un étang,” Élodie said—there’s a pond. She pointed at an island of light in the dark forest sprawling from the stone walls around the estate.

“We could walk to it.”

She shook her head. “On ne peut pas. There are wolves.”

Later, in the kitchen, as I helped Olga make dinner, I asked her about what Élodie had said.

“Non,” Olga said. “The wolves of France are long gone.”

Élodie, she told me, had suffered a bad case of pneumonia that spring and had spent a week in the hospital. Her lungs remained weak, leaving her susceptible to another infection.

“We must not overexert her with long rambles. And the forest is filled with spores and damp.” She was making a mayonnaise, whisking the egg yolk and oil in a bowl. “Élodie is stubborn,” she said, “an adventuress, like you. We used to picnic by the pond. I told her that a villager had spotted a wolf. Sometimes you have to lie to children to keep them safe.” She tilted the whisk in my direction. “Here, you try.”

It was then, over the making of the mayonnaise, that I learned how my mornings with Élodie would go. There would be no borrowing the Renault to take her for ice cream at the glacerie I’d seen as we drove through Benneville, no excursions to nearby lieux d’intérêt. We would remain solely on the grounds of the estate. “Because I miss her, you see,” Olga said, “though I have so much to do. I want to keep her close.” She touched my elbow. “Try to go a bit faster. You want the egg whites to conquer the oil or the mayonnaise won’t take.”

The next morning, I woke up to Olga’s knock on the door and her voice calling, “Il est huit heures, Brigitte.” I did a quick toilette in the adjoining bathroom, working my hair into a messy chignon and, since I was going to spend the morning with a four-year-old, putting on jeans and a T-shirt, which I’d ironed the previous night. These small details of domestic life—the ironing of everything, including sheets, the fact that milk was sold unrefrigerated and baking soda sold at the pharmacy, the smallness of toilet paper rolls, the gummy flaps of envelopes, the way Olga had asked me if I had my period because mayonnaise wouldn’t set if made by a menstruating woman, the grains of sea salt in the butter we ate with the daily baguette—made that first week interesting. One afternoon, Olga took me with her to do the shopping, and we stood in front of the counter at the Boucherie Marcel as she and the butcher—an old man with a lip curled by a scar—explained to me the different cuts of meat: tripes and brains and blood sausages, the thick steaks of horse flank. I bought a copy of the newspaper Libération at the tabac, learned the names of politicians, drank my water without ice, perfected my chignon. I felt that I was becoming French, that the transformation begun in a middle school classroom years before was growing into a truth. I would learn, by living with Olga, and Hugo, and Élodie, a new authenticity.

Breakfast, we ate outside on a lopsided table in a cracked and mossy courtyard. Hugo finished before the rest of us, and then he’d retreat to his study for the duration of the day to work on his biography of the Malagasy poet Rado Koto. A specialist in the literature of the French colonies, Hugo had not seemed attractive in the book jacket photo I saw when I looked him up at the BU library—a middle-aged man with too much forehead and not enough chin, eccentric tufts of hair, and drooping eyes. In flesh and in bone, though, as the French goes, he let off the sensuality of the brilliant. He ran the Études Francophones department at the Sorbonne. His book on the literature of colonial Africa had made him a Knight of the Legion of Honor. According to grad student rumor at BU, he had approached the department about a position, and they’d created one for him. Several heads shorter than he, Olga was stout and pudgy-fingered, with graying hair that thinned around her temples, and a pair of reading glasses always on a chain around her neck. I’d calculated that she must be in her late forties, a few years older than Hugo. She had teased him once at dinner that he’d fallen in love with her because she kept the ink cartridges of his stylos plumes refilled, and I wouldn’t have been surprised if this was true.

After Hugo had disappeared to his study, Olga would measure out Élodie’s medicine drops into a glass of water and grenadine. Then Élodie and I took a collection of books from the still-unboxed library back outside, to a bench under a chestnut tree that was covered by fungal growths, as ribbed and full as outcrops of coral. We’d sit in the shade for an hour or two, the sun ticking over the forest. As I read aloud to Élodie, translated, and answered her questions, I was often elsewhere in my mind, planning a weekend trip to Paris, imagining the apartment I would find for my August in the city, and then—turning the pages, saying car, voiture, moon, lune—the great workings of my future: an under-the-table job in a bookstore or café, a student visa, enrollment in a PhD program, an apartment with a view of the Seine, lovers, a perfect accent, fresh croissants every morning from the bakery on the corner of my cobblestone street.

“Regarde, Brigitte,” Élodie would say, looking up, “a bird.”

“Don’t move,” I’d whisper, and Élodie would whisper, “No moving.”

Above our heads, in the glossy canopy of chestnut leaves, a finch or sparrow rested on a branch, or worried a catkin with its beak.

“What does a bird say?” I’d ask after the bird flew away.

“Cheep, cheep,” Élodie would say.

The differences between animal noises in French and English made Élodie laugh. Why did a bird say cheep, cheep in English and cui, cui in French? Why did one pig oink and another pig groin, groin? Why woof, woof instead of ouaf, ouaf? Did a rooster that cried cock-a-doodle-doo know to cry cocorico instead if it moved to France? “Do rivers sound different in America too, Brigitte?” she asked me once.

Done reading, we’d take the path cut into a jungle of ivy and weeds back to the courtyard and leave the books on the breakfast table. Élodie would call out, “Maman,” once, twice, to the rear of the manor until Olga appeared from this window or that, like the cuckoo in the clock. “We are going for our walk now,” Élodie added, in English, as I’d taught her, and Olga would wave and tell us, in French, to have a good time and to be safe, as if we were heading off into the forest or along the road to Benneville, when in fact our walk would only take us around the manor and down the front drive.

The first night at dinner, Olga had told me the history of the property and of the surrounding area. Benneville had never been une métropole, she said, even before the destruction of the war. The village got its name from a monk on pilgrimage to the tomb of Saint Denis in Paris who, having stopped by the Seine for the night, cured a child of smallpox with his blessing. Over the centuries, the land around the village had been forested and used as hunting grounds for the royal party as an alternative to Fontainebleau. After the revolution, fields replaced forest. The commerce on the Seine moved to bigger ports such as Honfleur, and people mostly ma

de a living through sustenance farming. One such farming family produced a boy named Jean-Paul Léger, who joined the French army, fought in the Second Opium War, and, having learned the secrets of silkworm farming, opened a factory in Lyon and became the leading supplier of silk to the regime of the Second Empire. When Léger made his first fortune, he bought a large parcel of the forest where he’d played as a child to build a summer estate for his wife and son. Limestone from a quarry that later became the pond gave the façade its luminescent exterior. The walls of the manor were papered in silk from the Léger factory, and the ironwork of the balcony and of a pergola in the garden was designed to resemble silk thread. In addition to the manor, there was a cottage near the main road to house the estate’s servants.

Léger’s son, who inherited the property, had no children, his wife, the aforementioned grande horizontale, having broken her neck on the flagstones of the courtyard. The manor was “never quite so grand again,” Olga said. The next owner, an industriel named Émile Vouette, expanded the only real commerce in Benneville at the time, a sawmill on the Seine that had been converted into a nightclub. “You might have noticed the blinking breasts on the roof from the nationale,” Olga said. After Émile Vouette died, his widow eventually sold the former servants’ cottage and grew old alone in the manor. Her son, in turn, sold the property to Olga’s parents in 1943.

“They had tried to immigrate to the U.S. and were denied visas,” Olga said. “So they came here. I suppose they thought they’d be safe this far from the city. They had forged identity cards and millions of francs in cash. But they were arrested by the Gestapo soon after they moved into the manor and were sent to Drancy.”

Olga’s mother was pregnant at the time of the arrest, and Olga was born in the camp. A worker, later hanged by the French milice, smuggled the baby to safety in a laundry cart. Olga was raised in an orphanage in Paris. After some legal battles, the property came to her as the legal owner. The manor had been destroyed by looters during the war, Olga’s parents’ belongings sold on the black market. “Nothing remained,” she told me, except for a set of wooden nesting dolls—the outside figure an old woman in a red and yellow sarafan—that stood on Élodie’s nightstand. The dolls, Olga said, were originals from Abramtsevo, near Moscow, where her parents had lived before moving to France. “Someone must have put them back.”

The Balcony

The Balcony