- Home

- Jane Delury

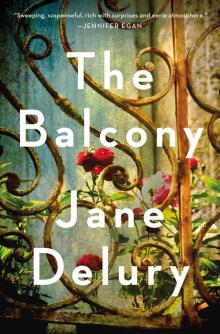

The Balcony Page 18

The Balcony Read online

Page 18

“It’s that way,” she says, and then, “I’m used to guiding people to the right place.” She tries to laugh, and I realize I’ve only imagined she knows. And what is there to know anyway?

Or

You are my husband, I remind myself the next day. I’m in the life we’ve built and it’s a good one. You fix problems he never could: there you go to the phone to tell the contractor that the bill for the roof is wrong. “I’ll go pick up a pizza from the truck on the square. You look tired. Don’t cook.” Goodbye, goodbye! I’ll see you later. Down in the kitchen, I draw with the girls at the table. The painters have moved on to the trim of the third floor. The floor of the parlor has returned to a checkerboard, and the soot has been cleaned from the fireplace mantel. We’ll sit by the fire during the winter. We’ll host parties like they do. We’ll get wrinkled together. I’ll be content. Who wouldn’t want this? If I were walking a railroad track and a train came from nowhere, you’d throw me aside and take its weight.

Later, as night falls, we sit in the pergola, facing the forest. You hold my hand and I lean my head on your shoulder. Anyone looking at us would think we are perfect, and I suppose that we are.

Let me tell you how I see the forest now, after having seen it during my childhood as a jumble of trees. Those branches that snake between the leaves resemble the veins and arteries that pull blood to and from the heart. All of life depends on such passages. Think of my breasts a year ago, when I was nursing. Milk through ducts. Footpaths through trees. The eye, too, is fed by a network of vessels, but his eyes have grown unnecessary roots. They swell and burst, creating a bulge that he sees as a dark spot in the center of his sight. His peripheral vision remains perfect, so when I walk at his side, he can see me.

Before we came outside to sit together, I put the girls to bed with Le Petit Prince. Do you remember what he says when he meets the fox?

“It is only with the heart that one can see rightly; what is essential is invisible to the eye.”

And

How much is magic and how much is magic tricks? I keep thinking that if I look in the hat, I’ll find the trapdoor to the rabbit. Every gesture, every word out of your mouth, has become a clue to a mystery that I might have invented. Today, when I meet you at the pond, you’re skipping rocks.

“Try it,” you say. “You look lucky today.”

What does that mean? Later, as we walk a trail, your arm presses into mine. Was that an accident? A hand on my back over a stretch of moss. Careful, don’t slip. When I’m the one who should be guiding you.

I let you see what you see, though I know I’m seeing what you can’t. Details: the curl to a leaf, a trout that flips out of the pond. Pine needles flow over our heads. You tell me about a conference you’ll go to next month.

“I can’t operate anymore,” you say, “but I can talk about operating.”

Then you mention that you might write a book on a technique you invented. You could go into the heart softly, with needles, not knives. I say you should. You can’t have my body but take my opinions.

“I’m catching it,” I tell you when I see the toad. It leaps ahead into the camouflage of fallen leaves. I put it in your hands.

“Funny,” you say. “It feels like a heart.”

“Your fingers don’t ever quiver,” I tell you.

“Years of training,” you say.

Then the backs of your hands in my palms, telling me, Open. That cold ball of flesh that trembles with fear, unsure where it has come to.

And

Here’s what could happen: Tomorrow afternoon when the children are with the nanny and I’m supposed to be driving to Paris for a chandelier, I come to your cottage. We lie in that bed. I kiss your eyes and your chin and your cheeks and your ears and your neck. Your steady hands hold my back.

Or

Here’s what could happen. I don’t tell you.

And

Or I tell him.

Or, And

Then what?

And

It’s time, he says, to reciprocate your wife’s dinner invitations. I make deviled eggs. I make meatloaf. All of this food that I don’t want to eat. I feel that I could never eat again. The sound of the door knocker stops my breath, but I continue to set the table. The girls drag on my legs: “Mommy, Mommy.” Your wife gives them chocolates wrapped in cellophane, which they rip open and eat cross-legged right there on the floor. Despite all the commotion, I’m quiet inside. I pour you a drink.

“You look nice,” you say.

My house and my children melt away, and then re-form when the baby cries. In moments like this, when I pick him up and he grabs my hair, my compass shifts back to its center.

He suggests a tour of the manor. I watch you as he puts his hand around my waist. Your eyes flinch.

“She gets the credit for everything,” he says. “She’s done magic.”

In the parlor, he points out the nesting dolls on the fireplace mantel, and the relief carved into the stone. “They look like butterflies,” he says, “but in fact, they are silk moths. And those are mulberries, though they look like grapes.” You move closer out of politeness, but I know that the pattern hides under a cloud that will grow thicker each year until it covers your world completely.

“Let’s have the aperitif upstairs, on the balcony,” I say. “That would be more festive.”

I have the baby in my arms, and yes, I know what I’m doing when I ask him to get the drinks. You ask her, “Could you lend a hand? You know me and stairs.”

This is the first time we are cruel together.

I leave you in the hall to put the baby in his crib. We climb the stairs, side by side. You find the handrail for yourself.

“It’s not finished,” I say when we get to the room.

“You’ll get there,” you say.

On the balcony, I stand in your peripheral vision, perfectly focused. You lean toward me, and I lean toward you, and our hearts line up to beat together. Inside the house, the baby is crying. My hands on your back are as steady as yours on mine. And all around us, there are nothing but trees.

Acknowledgments

Thank you:

To my daughters, Margot Deguet Delury and Rose Deguet Delury, for their joy and encouragement and for being them.

To the rest of my family, John Patrick Delury, Cecilia Delury, Vince Jacobs, Jeong-eun Park, Sean, Senna, and Hannah Park Delury, Pat and Mimi Kearns, and John Francis Delury. Thanks, too, to Anton Deguet and his family, Gilles Deguet and Françoise Valtrid, Joris Deguet and Marie-Claude Dupont, and to Camille and René Deguet, who first showed me the forest.

To Jean Garnett, for being a dream of an editor, and Reagan Arthur and the entire team at Little, Brown. I could not be luckier to have my book in these hands.

To James Magruder, Marion Winik, Jessica Anya Blau, Elizabeth Hazen, Elisabeth Dahl, Liam Callanan, Peter Grandbois, Kathy Flann, Christine Grillo, and Stephen Dixon and Alice McDermott for reading and editing me.

To Kendra Kopelke, Stephen Matanle, Betsy Boyd, Emily Gray Tedrowe, Laura van den Berg, Madison Smartt Bell, Gabriel Brownstein, and Paul Yoon for their writerly support.

To the organizations that have helped my fiction along: The University of Baltimore, VCCA, the Johns Hopkins Writing Seminars, the Maryland State Arts Council, and to the editors who have taken such care with my stories, in particular Tom Jenks, Cara Blue Adams, Linda Swanson-Davies and Susan Burmeister-Brown, M.M.M. Hayes, and Jeanne Leiby.

To my wonderful agent, Samantha Shea, and Anne Borchardt and the entire Borchardt agency.

To Don Lee, who believed in this book and in me and was with us every word of the way.

About the Author

Jane Delury’s fiction has appeared in Narrative, The Southern Review, The Yale Review, and Glimmer Train. She has received an O. Henry Prize and holds master’s degrees from the University of Grenoble, France, and the Johns Hopkins Writing Seminars. She teaches at the University of Baltimore.

Th

ank you for buying this ebook, published by Hachette Digital.

To receive special offers, bonus content, and news about our latest ebooks and apps, sign up for our newsletters.

Sign Up

Or visit us at hachettebookgroup.com/newsletters

The Balcony

The Balcony